To Prove My Love

01/29/2015 17:19

“You will be waiting for me many days, but you are not to take any other husband or lover.” Hos. 3: 3

Blessed Guerric quotes the prophet Hosea to express that the life of a monk is one of suspense. He also describes this life of suspense as a “suspended death” on the cross. Surprisingly, Guerric says that "He is most happy who is waiting in such suspense..." How can this suspense be a pleasant experience? The first time I read this sermon I was incredulous, but after mining my own experience I came upon a memory that changed my mind. The memory is actually quite personal, but it suffices to say that knowing that God is pleased by an individual’s fierce fidelity makes any suffering meaningful and even sweet. If it pleases my Lover for me to prove my love, then prove it I shall, sweetly and suspended on the cross.

Br Luis Cortes, Vina

You Will Not Disappoint Me

01/13/2015 10:21

“We are waiting for the Savior.” Such waiting is truly a joy to the righteous who are waiting for the hope of blessedness, the glorious coming of our great God and Savior Jesus Christ. “What am I waiting for,” a righteous man may ask, “but the Lord?” “I know,” he says, turning towards him, “that you will not disappoint me after such a wait as mine.”

Confidence. Trust. Hope. Joy. It is all matter-of-fact for this person. In his relationship with Jesus there is absolutely NO DOUBT that his Lord will come with merciful love and salvation. Wow! I read the words of Bl. Guerric and the joyful longing is contagious. “That’s how I want to be!” I say, and I am eager to wait upon the Lord.

And yet I have a certain character flaw, that without God’s grace I often wait in anxiety, even for good things, instead of waiting in hope and excitement. No one would necessarily notice this; it is a vice fueled by cultivating unspoken doubts such as: “What if things go wrong?” “What if I am disappointed?” “What if I am rejected?” “What if I am not worthy?” “What if I am mocked by others?” With this awareness I have to ask myself, “What in the world are you waiting for?” because it would seem that I am waiting for, and expecting, only disappointment, rejection, and mockery.

St. Benedict calls the monastery a “school of the Lord’s service” and so it is here I learn to serve and wait for the Lord in joy, hope, excitement, confidence, and trust. I learn this first of all from my sisters. Their fidelity to a life of charity is a mirror of Christ’s fidelity to us. Their steadfast and forgiving love allows me to learn trust and confidence. The daily practices of prayer, chanting the psalms, meditating on God’s word, all provide good fodder for my thoughts, replacing the habitual doubts that try to sneak in. And God’s ABUNDANT graces prove him true. Promising myself to Jesus at my solemn profession I had absolutely no doubt that my Lord was receiving me with merciful love and salvation. I could turn towards Jesus in full joy and confidently say, “I know that you will not disappoint me after such a wait as mine.” As St. Paul says, “hope does not disappoint us, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit which has been given to us.” (Rom 5:5)

Sr Myra Hill, Mississippi

Impression

01/09/2015 14:58

Waiting. Expecting.

Texture of words. Feel the sharp edges of the consonants in expecting, the long extension of the vowel in waiting.

Feel with the soft tissue of the mouth. Taste.

Words as eggs, filled with remembered associations. Yolk of meaning nourished by the white of experience.

Waiting: bleak, empty, oppressive, passing time, blank, absurd, senseless.

Expecting: piquant, vibrant, hopeful, fertile, with child -- someone is coming.

Assured coming. Piqued interest. Sitting on the edge of my seat.

Vigilant. Sharply aware Sensitive to signs -- the winter landscape is alive with possibility.

Br Cassian Russell, Conyers

He Will Come

01/06/2015 16:42

Times of waiting are an intrinsic part of life. In all of life’s events – both the great and the seemingly insignificant -- some things happen spontaneously and at other times, we must wait. When we wait, we do so because we are not in a position to immediately change a current situation to suit our liking. We are at the mercy of circumstances and Divine Providence. By remaining in a situation where I lack what I desire now, I exercise hope and trust that by patiently waiting, what I long for may be realized. If, in a particular situation I ask, “Should I wait?” and then decide to wait, I do so because I am convinced of the importance and necessity of waiting for what is to come.

Experiences of waiting are a definite choice and are not necessarily an automatic action or reaction. In some times of difficulty, waiting could end earlier by choosing an alternative, which may seem to be easier momentarily. Hoping and believing that the decision to wait is the best one (if not the easiest or quickest) means a deliberate choice to endure and not to give up and walk away prematurely out of frustration.

In a time of great interior struggle or difficulty, a person can choose to patiently wait (or not to wait) for God’s action in their life. It may seem that the only thing to do is to beg God for His grace and mercy to transform the situation and our inner being. We can only wait and pray. Endless questions may assail: “Will God change this situation? What does God want? Will He make the path clear to me?” Waiting for God’s movement in our lives can seem endless, hopeless, difficult – even painful – because we do not know how (or believe that) it could possibly even change.

Even if we may sense that there is no clear end in sight for a very long time, we can still choose to wait patiently for God to act or to reveal His will in a particular situation. Waiting in these times is an experience of hoping against hope or living in the “bare hope” that Guerric references. After a prolonged waiting with no end in sight, the question in one’s heart can then become, “How much longer will this time of waiting last? Is it foolish to keep waiting? Do I have the strength to continue to wait? Did God forget me?” Our expectation of a sooner response or resolution may be not so forthcoming. It is at times like this when Guerric says we must be faithful to God. He refers us to the book of Hosea where the bride is told, “You will be waiting for me many days, but you are not to take any other husband or lover.” Guerric says we must imitate this response of love and faithfulness in times of trial, too.

Perhaps it is easier to wait with joyful expectation for something with some (more or less) definite arrival time – waiting for springtime, a birth, an imminent death or other transition of life. We know that with some degree of certainty these events (cycles of nature, of life, of humanity) will take place eventually. We have a clearer sense of what we are waiting for and what is expected and of our own capacity to respond and to be ready.

Waiting for God in times of great trial and profound mystery teach us to hope and trust in our loving God who does not forget us and who has a plan for each of us. In our obedient passivity and receptivity we give God the freedom to act and to be in control of our lives and our future. We cannot rush Him. The Psalmist perhaps says it best: “I waited, I waited for the Lord; who bent down and heard my cry”. (Ps. 39/40:2) Yes, wait for him. Let us be faithful and if, at times, your life seems to be and endless Advent season, be patient and wait for the Lord. He will act. He will come.

Sr. Francesca Molino, Wrentham

Inmost Waiting

01/05/2015 16:07

“I shall go on waiting for him confidently” (Adv1:3)

Guerric opens his sermon, focusing on ‘for whom we are waiting’. The Savior, Jesus Christ, our hope, joy and all! ‘Waiting for the Lord’ is the very essential disposition of Cistercian life in every aspect. We are waiting not only for his final coming but also daily coming, since as his own, we have been falling in love with Him helplessly no matter how deep or strong, how feeble we are. We long to see and hear, to taste and smell ‘for whom our soul waits and in whom our hearts rejoice’ (Ps 33:20-21). It is our final bliss and daily bliss as well.

The initiative of coming, however, belongs to only God. This truth puts us in suspense for his return. “I shall go on waiting for him confidently” (Adv1:3). Guerric strengthens us firmly, inviting to exercise patience and to keep the troth. It is not easy to watch or to stand faithfully in life-long suspense. If we are wise, it would be an excellent time to earn every virtue, heavenly treasures, and spiritual charity for us and others, with our watchful prayer and sweat of love.

Waiting confidently is like seeking God unceasingly, as the lover in the Song of Songs; “I was sleeping, but my heart kept vigil” (Sgs5:2). Her plain self-knowledge is similar to the reality of our journey of waiting that is still unready to open quickly, due to our fragility, though our heart is ready. Waiting in confidence is also rooted in deep trust in God’s intimate love. He never abandons whoever waits or thirsts for him. Indeed, He is the one who is eagerly waiting for the most timely day, for the most timely moment in each of our days.

He knocks, I say ‘daily’. “Open to me…For my head is wet with dew, my locks with the moisture of the night” (Sgs5:2). This beautiful word has strongly affected my daily waiting for the Lord since I began monastic life. It deeply reminds me of Jesus Christ, often praying alone on the mountain at night before dawn, in the dew time of cold. He was staying awake all the time until death on the cross. We follow his deepest waiting for his Heavenly Father.

We are beings willingly hanged on the cross by monastic vows. It is there, in which we are waiting for the Savior with inmost heart day and night. It is there, we hear his knocking, “Open to me, my beloved!” If we open, our whole being will be in his bosom, and be moistened with his full dew of heavenly grace, like a being simply in the unknowing cloud. This is indeed our hidden way of waiting, inviting the human race ‘to raise the hope above earthly concerns.’ (Adv1:2)

Our Savior was born to us, ‘like dew from above, like gentle rain He drops down (Is45:8)’. God is with us. Let our inmost heart be deep moistened and softened by the quiet, gentle breathing of Infant Jesus and his grace. In his wondrous Name, let us go on our journey of waiting evermore confidently in a deeper way.

Sr.Cathy Lee, Santa Rita Abbey

Pregnant Waiting

12/23/2014 10:46

Compare waiting in a doctor’s office, or for a webpage to load, to eagerly awaiting reunion with the one you love. The first fills us with an oppressive sense of restless passivity. There is a banalization of time we do anything we can to escape: scrolling through our phone, thumbing the heap of glossy magazines on the waiting room table. In the second kind of waiting however, we savor the interval. Whenever our mind wanders we delight to recall the memory of the one we await; and that he will soon be here.

Guerric describes waiting that is a “joy.” He uses the word “laetitia” which also has the sense of “fat, rich, fertile”: a “pregnant” waiting. Someone described monastic life as “a vast and fruitful loneliness.” The vast and fruitful lifelong waiting of the monk is full of suspense. The monastic practices all cultivate the “memoria Dei,” like a lover reading through old letters, gazing on photographs to kindle and refresh his longing for the one he awaits.

Such waiting is a “joy” because we are waiting for one who has already come. “Already my being is with you.” Our true nature is already lodged in the glorified Christ and we have only to wake up slowly to where we already are. His coming to us is our coming to him; it is our coming to ourselves, awakening in his light. Bernard writes: “In giving me himself he gave me back myself.” We “come to ourselves” continually, from the prodigal son’s “coming to himself” in the land of unlikeness to the full realization of our true self “hidden with Christ in God.”

Monastic life unfolds in an exquisite, agonizing suspense… punctuated by the occasional foretaste of reunion. “In a dark moment [the monk] is taken, suddenly like a hooked fish or an ensnared bird”; we forget ourselves completely, snatched up into the Other.

The english translation given here for “expectatio” is “waiting”; like “expectation” it suggests a more passive stance toward an absent reality. The french translates with “attendons, attente;” we are attending a Savior; paying attention to, waiting on…one already present, if “in a mirror dimly.” We hold ourselves in readiness, poised to act at the least indication of the Lord’s will, waiting on and attending to the needs of the poor in our midst.

The quality of our attention to the signs of his presence, our refusal to distract ourselves, to break the suspense of waiting, makes the difference between a life spent waiting helplessly for a webpage to load and one of eager, active longing for reunion with our beloved.

Fr. Isaac Slater, Genesee

The Latent Power Of Patience

12/23/2014 10:43

We live in a consumer society which not only promises, but actually delivers, instant gratification of our desires. 1 Click on Amazon and it is yours, shipped immediately from a Fulfillment Center and guaranteed to arrive within the briefest possible time. Twenty-five years ago, the rock band Queen voiced the expectation that technology and marketing have since literally delivered: “I want it all / And I want it now!”

What effect does instant gratification of our desires have on us? It deprives us of the experience of exerting the latent power of patience in hopeful waiting. To those who never wait, patience is never needed. But patience called forth by waiting in hope builds both expectation and anticipation of the joy experienced when the end is finally attained, the goal reached, the prize received.

Our Advent hope rests upon the assurance that “although (the Lord) does command that he should be awaited with patience, in another place He promises that He will be coming quickly” (Guerric of Igny, The First Sermon for Advent). With these words, Guerric invites us to remember that the Lord promises not immediate gratification, but the opportunity for our expectation to grow in patience from both the yearning created by His command to wait, and by His promise that what we already possess in faith will be quickly ours – “though it may well seem very long to any of us who are in turmoil, whether from labor of from love.”

In fact, it is the Lord’s waiting – His patience with us, hoping and expecting that we will respond to His love and mercy revealed to us in Christ – which encourages and sustains us as we await His coming. Blessed indeed may we be who wait for the Lord, but more blessed be the Lord who waits for us.

Fr Ed Hoffmann, Snowmass

In-between

12/23/2014 10:32

“You chose to hang from the cross, so that being raised up over the earth you might draw us to yourself and hang us also above earthy concerns.” (4).

*************************

This image of hanging on the cross with Jesus touches me profoundly as it truly names my experience. Living our Cistercian life is like hanging on the cross in a kind of suspension between consolation and desolation.

There is this enormous tension in the experience of this in-between. Somehow you must respond with fidelity to our life with openness to the Spirit within. It is a real suffering, living in this tension because the consolation of the early monastic experience has quietly departed and the call to steadfastness in the midst of a feeling of dryness is overwhelming. This is hard to sustain without discouragement and a movement toward desolation.

The one blessing is the daily routine of community, prayer, and work that gives shape to our life of doing the Will of God. We have responded with a commitment that is strengthened and enlivened now by acts of faith, hope and love.

Seeking to discern the state of my spiritual journey, I am confronted with the finality of Solemn Profession. With all the joy that Profession brings there is a discordant note. This is it now. Stability has me here, obedience defines my existence, I have limited my options. But wait a minute – this is exactly what I wanted to do - God’s Will was so clearly inviting me to this life. Why this struggle, this hanging on the cross feeling when all I want to do is give myself to God alone, to live with the promptings that come from my true self. These promptings of the Spirit within have been so consoling, so joyful, so empowering.

But here I am living the vows. Living our life is like the Passion, a dying to self in every way. Yes, the poverty of our Cistercian life can be truly overwhelming, but it’s our way to seek God, to seek holiness.

Hanging on the cross is waiting, waiting for the Lord, like the deer yearning for running streams, we yearn for the Lord to come to save us. So why are you cast down my soul, hope in God, I will praise Him still, my savior and my God. (Ps 42)

Fr Joe Tedesco, Mepkin

Salvation Paradox

12/23/2014 10:03

Salvation Paradox: With Yet Longing

In the opening of his sermon Bl. Guerric crisply identifies the paradoxical relationship a Christian has with God, “Already my being is with you”[1] while at the same time, “…all flesh will come to you, the members following their Head, so that the holocaust may be complete.”[2] We are with Christ while coming to Him yet we wait to be completely with Him. Christ’s refinement occurs in time. He is with us as He grows our capacity to give ourselves to Him and to receive Him. There is some “end point,” where our submission to Him will be absolute, allowing us to experience the fullness of His submission to us, “Our abiding place is in heaven….”[3]

That Christ works in time is a central feature of the salvation paradox. Time implies movement. Guerric points out that the waiting he discusses is not static. It is a process. The process of salvation unfolds as time moves forward:

1) In the present, men and women of Christ wait with Him as we are refined, in the hope of receiving Him more fully,

2) In the future, we submit fully to Him and fully receive Him when His work is completed.

Graced movement is more toward fulfillment in Christ. On the other hand, not following God’s grace leads toward fulfillment of self desire—fulfillment in the world. Those who hold Christ as their prize wait with Him. They experience His presence, though not fully until His work comes to completion.

Paradox Rather Than Ideal

Ideals generally delineate some sort of perfection; conditions where everything is as it should be or at least so close to such a state that any deviations can be quickly eliminated and perfection efficiently restored. Sounds good—as long as we remember that ideals are concepts and concepts are abstract; and as abstractions, ideals can never reflect all aspects of a real situation. [4] Ideals often are attractive. It can be easy to react to Guerric’s first sermon by reading it as a statement of an ideal rather than a paradox. Thus it may be easy to conclude that we should live in joyful anticipation and therefore there is something wrong with the pain of longing to experience Christ more fully. This would be analogous to looking at only one side of a beautiful coin and to prefer it to the extent of overlooking the other side, which can have its own beauty—its own graced impression, its own worthy qualities.

Another analogy might be a man who is with his wife and child on a wonder-filled holiday. He is living in the joy of his family. He is fulfilled; a lovely setting. A year later, the same man finds himself in a foxhole on the battlefield of a terrible war. He pulls from his pocket a picture of his wife and child. He feels their love for him and his love for them. He may feel this love more powerfully than he ever has, yet something of his family is lacking. He longs for the fulfillment of their presence in a way he does not have on the battlefield. Still this second scene has beauty—the beauty of love in the midst of tragedy. The scene demonstrates a beautiful paradox; love’s “presence in absence.”

We are with Christ in His presence and as well in our experience of His absence. We have Him who makes life worth living yet we desire to experience more of Him. St. Paul expresses something like this when her writes to the Philippians, “to live is Christ, to die is gain,” and tells the Corinthians he lives with a “thorn in his flesh.” The thorn is allowed by God—in essence refining Paul and growing his experience of God and His power.

Guerric elaborates reasons that God allows unfulfilled holy longing. Among them are to:

1) Grow hope, patience and persistence,

2) Strengthen the believer’s humility, and recognition that God Himself is humble, “They recognize the divine majesty humbled in the flesh…,”[5]

3) Allow for repentance of sin, more complete conversion and growth in virtue,

4) Increase the gift of His mercy to us, “If you are a sinner, do not be heedless but take the opportunity to repent. If you are holy the time given to you to progress in holiness,”[6]

5) Develop in the believer the kind of fulfillment born of increased anticipation and a prolonged duration of longing, “we wait for you…to come and take us up.”[7]

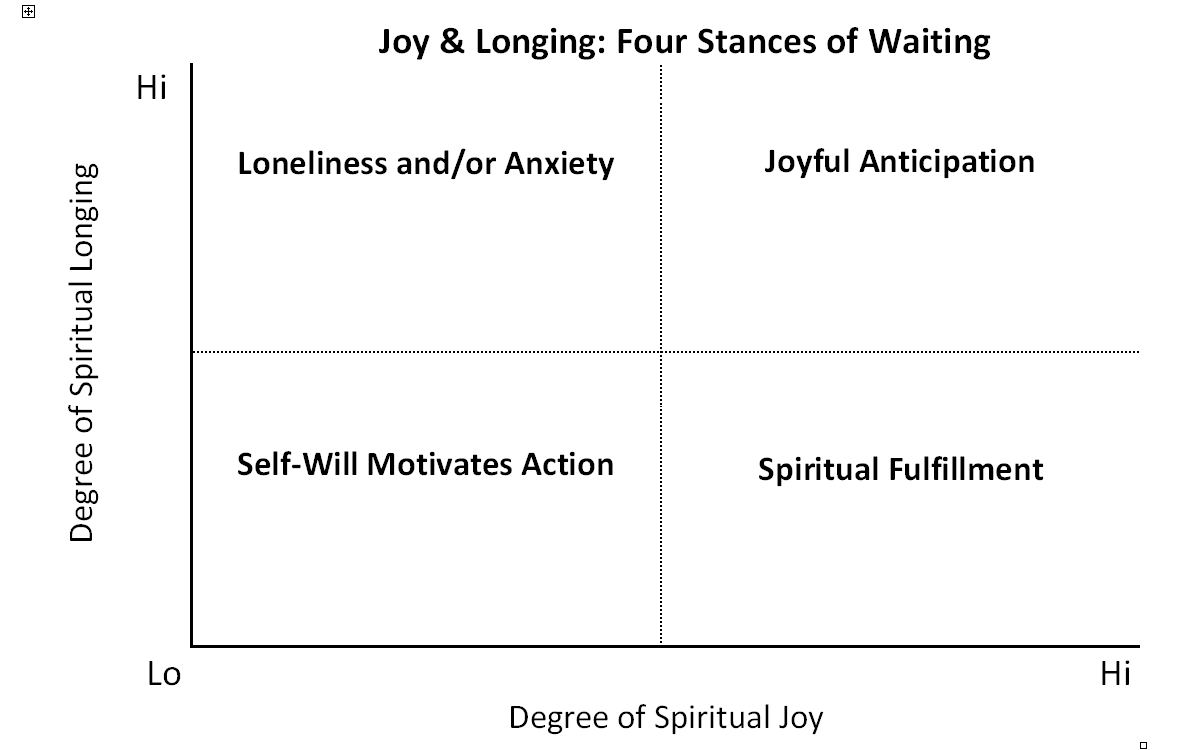

A Proposed Model: Four Stances

Some may find the model below useful for practical application of the salvation paradox. It may offer light on why the uncomfortable states of loneliness and anxiety can exist while waiting in faith to receive the fullness of Christ.

The model illustrates how different levels of spiritual joy and different levels of spiritual longing result in different stances. Central terms are described below:

Spiritual longing is a graced sense of desire to answer Christ’s call to be with Him more completely.[8]

Spiritual joy is a graced sense of contentment with the degree to which God has developed us to allow fuller submission to Him and fuller reception of Him.

When “high and low” conditions on each of these dimensions are compared to one another, four general stances become possible. [9] Broad descriptions of these stances appear below:

1) Loneliness and/or Anxiety, where spiritual longing is high and spiritual joy is low,

2) Self-will motivates action, where both spiritual longing and spiritual joy are low,

3) Joyful anticipation, where spiritual longing and spiritual joy are both high,

4) Spiritual fulfillment, where spiritual longing is low and spiritual joy is high; we are completely with God and completely content.

Both spiritual longing and spiritual joy are graces which we can prepare ourselves to accept, but ultimately they are gifts from God. Perhaps the simplest prescriptions to incline us to answer God’s call to grow in spiritual longing and in spiritual joy are prayer and acts of love. Prayer and acts of love both bring us more to the presence of God. Faith tells us this is so even though we may not be contented with the sense of God’s presence when we pray and perform acts of love. Thus, one possible state of spiritual longing is loneliness and anxiety. Spiritual longing may leave us feeling dry, but faith in prayer and acts of love must trump our senses if the focus is spiritual growth.[10] There are a number of reasons why God may allow loneliness and anxiety for those who truly long for Him. Among them are that God may wish to:

1) Make us more aware that our sense simply is not accurate and needs to become more attuned to His presence in our lives,

2) Use loneliness and anxiety as a call to greater submission to and reception of Him,

3) Grow our faith,

4) Call us to more deeply feel our poverty and need of Him,

5) Develop us in several of these areas.

Let’s revisit some of Guerric’s reasons God grows holy longing and consider their implications in the framework of time:

1) Renunciation may need to grow (and this growth occurs at least in part over time),

2) Patience and persistence are practiced in time,

3) God’s humility is often revealed more and more over time,

4) Repentance can grow in time and more complete conversion occurs over time,

5) Increases in God’s mercy occur over time.

To fine tune our understanding of a sense of dryness in spiritual life, one useful question may be, “How is God trying to grow me so I may submit more of myself to Him and receive Him more fully?”

For Further Consideration

If you have found this discussion strikes some cords of recognition, you may wish to consider some questions:

Do I find this model helpful in some ways? If so, how? If not, why not?

If this model might be helpful to you, where would you place yourself given your own development in the areas of spiritual longing and spiritual joy at this time? At other times that were significant to your spiritual development?

Our levels of spiritual longing and spiritual joy can change depending on the issues we may be grappling with at a particular time. Is this so for you? What kinds of change do you notice with different issues? What does this tell you about your spiritual growth and your relationship to God and your community?

Does Blessed Guerric’s First Sermon for Advent give you other ideas that might help you open more to God when he calls you to increase your spiritual longing or your spiritual joy?

Br Mario Schemel, Conyers

[1] Cistercian Fathers Series: Number Eight, Guerric of Igny Liturgical Sermons, v. 1, translated by monks of Mount Saint Bernard Abbey. Cistercian Publications: Spencer, Massachusetts. (1970). p. 1.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., p. 2.

[4] A general problem in being unmindful of this quality of ideals is that it can lead to unrealistic expectations. At best, such expectations lead to disappointment when we fail to meet them or to unrealistic evaluations of the extent to which we as individuals or as communities live by the ideals we are striving to maintain. Further forgetful that ideals are rarely fully attained in life can incline us to two dangers. We can suffer undue disappointment when we fail to meet our ideals, leading us to a misguided humility formed by an unrealistic frame of mind. On the other hand, our desire to fully live our ideals may be so strong that it blinds us to significant ways we are falling short of them. Both errors sell humility short. Humility is a dangerous virtue to sell short, because as pride is the primordial evil and always somehow intertwined with all other sins, humility is a foundational grace; a condition preceding or developed simultaneously with all virtue. Thus selling humility short runs the danger of thwarting the development of virtue.

[5] Ibid., p 2.

[6] Ibid., p 3.

[7] Ibid., p 5.

[8] Note the assumption here is that at some point redemption will be experienced fully—salvation will bring us completely to Christ and Him completely to us. Thus there will be no more desire to be with Him more fully as we will eternally be with Him in full. In this state, spiritual longing as described here will cease to exist, and spiritual joy will be complete.

[9] These categories are a “rough” division with permeable boundaries. There are obviously a large number of possible states allowed by the matrix, and naming each one would be a difficult task. We do need to recognize that each person’s place in any scheme may follow certain patterns but is unique, and that while recognizing general patterns of development is helpful, tailoring interactions to individuals and their particular situation is more useful still. Note that for a “pure” stance, a stance would have to fully reflect its description, containing no qualities of another stance. Short of this, a stance reflects at least some of the characteristics of some other stances. Thus, for example, complete joyful anticipation would require full spiritual longing and full of spiritual joy. It is reasonable to question whether many attain this state in this life. This being so, most of us at least at times feel some dissatisfaction with the state of our presence to God and the degree we sense His presence to us.

[10] One brother recently remarked to me:

“To me dryness in prayer is a positive. Contemplative union transcends the senses, and dryness involves a lack of feeling that God is present. The absence of feeling is not a negative, but a positive. It is inner silence, which is the essence of contemplation—no subject-object split, pure [inter-]subjectivity. Oneness—one, yet two. There is no ABOUT. When we speak of an experience OF or about God, that is not contemplation.”

We each of course have our experiences of Our Lord and our descriptions of these can never be complete. Above, the brother appears to describe dryness in contemplation as a state of higher spiritual longing and lower spiritual joy—something akin to loneliness in the model I propose. The brother’s remarks can be interpreted as adding a different dimension to the factors I explore here, and he is certainly not alone on this point. Another possible interpretation of the situation he describes is that perhaps during contemplation more than one thing may be occurring, at least from time to time. One thing happening would be the experience of contemplation itself. Another thing could be the human reaction to the contemplative experience. This reaction could encompass a sense of joyful anticipation, or spiritual fulfillment, or loneliness. The brother’s remarks and the possibilities they propose for understanding contemplative experiences are worthy of a more in depth examination than the scope of this short paper allows.